The Botany of Beer

By Joseph Alton

September 22, 2022

Unlike its grape-based cousin wine, beer as we know it today has evolved far from the beverage’s first iterations. Depending on who you ask, beer has been produced (intentionally) for somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 years. But the world’s most ubiquitous alcoholic beverages weren’t always brewed with the familiar trinity of barley, hops, and water.

In fact, almost every culture from across the globe has used different native plants to produce fundamentally similar but practically very different versions of their own fermented beverages.

Though barley was cultivated for brewing in Egypt and Mesopotamia as far back as the 4000 BCE, other parts of Africa used millet, maize and cassava as their fermenting starches. Native North Americans used persimmon. Central and South Americans used agave, corn, and some varieties of tubers. The Chinese used wheat. The Japanese brewed with rice. Other Asian cultures used sorghum. The Russians, rye.

But not one of the beverages crafted by these cultures used hops as a flavoring agent. Hops aren’t said to have been introduced to beer making until Benedictine monks began using hops for brewing in the 8th century.

So, what did pre-800 AD humans use to add flavor and balance to these ancient ales?

ALL THE PLANTS.

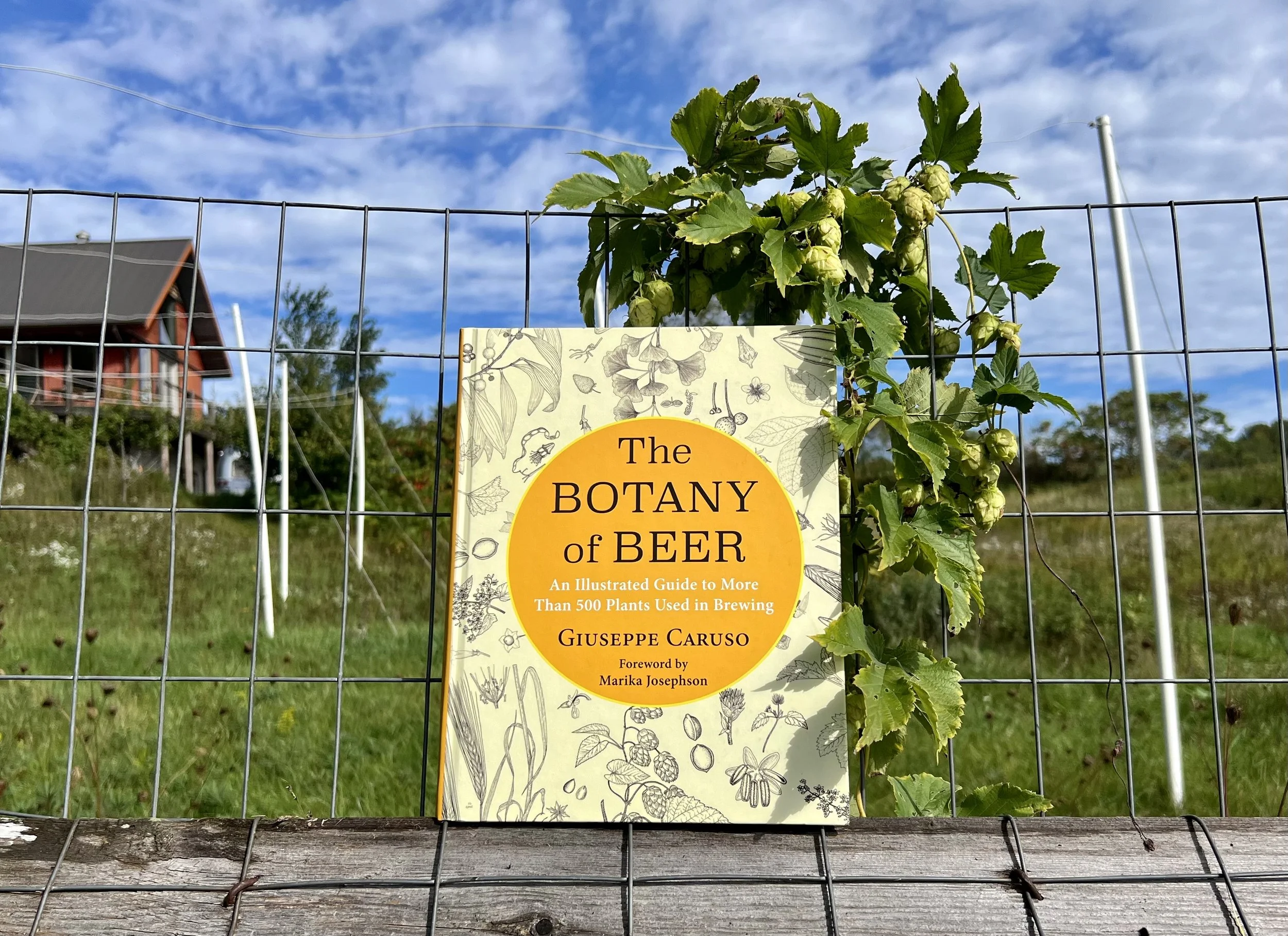

In Giuseppe Caruso’s The Botany of Beer, we learn that through history, “hundreds of different plants were used to make beer.” Caruso explains, “plants used in brewing were the hallmark of the region where the beer came from, and a mix of wild and cultivated herbs.

“There are many thousands of years of ascertained beer-making, and most of those millenia are without or mostly without hops,” says Caruso. But he doesn’t blame brewers old or new. “With hops having so many useful qualities for brewing in one single species, it was frankly inevitable that hopping would become a systematic practice.

He encourages us though to imagine a less globalized, less homogenized brewing landscape where unique local ingredients are featured and celebrated. What he sees as a trend towards localization will continue to emerge in the brewing industry. Think “Slow Food,” but for beer.

Breweries are escaping what Caruso calls the “gilded cage” that is hops, and research and attention are increasingly being allocated to a wider variety of beer-making ingredients. “Faced with a seemingly endless availability of products and beer ingredients and the effects of globalization, there are those who believe it is more ethical, more functional, and even more convenient to use local products.”

So we should stop using specialty malts from Germany or hops from the Pacific Northwest in our beer? Of course not. But Caruso’s book highlights the boundless opportunities we as brewers have in the natural world.

“When freed from ties with a cumbersome beer-making past, it is possible for creativity to wink at other more deeply rooted traditions.

His book, recently published by the Columbia University Press, is a comprehensive but practical compendium of the characteristics and properties of more that 500 plants used in making beer, accompanied by the author’s hand-drawn ink images.

As the founder of Botany BrewFarm and a new “BrewFarmer,” I was obviously drawn to this title, and The Botany of Beer doesn’t disappoint. It is a well organized, useful directory of familiar and unfamiliar plants from North America and the rest of the globe. It has already served me and my brewing team well in conceiving new beer recipes, and has been useful in helping identify which of the plants grown on our 35 acres may someday make it into a batch of Botany BrewFarm beer, mead, wine, or cider. We’ve already identified more than 50 different plants growing on the BrewFarm that Caruso’s book classifies as beer ingredients.

We can’t wait to showcase nature’s vast array of wild and cultivated flavors — honoring the brewing traditions of yesteryear while crafting our own.

Want to learn more about the botany of the BrewFarm? Follow our project on iNaturalist, where we have started indexing (and geo-tagging) all the species of plants growing on the property, and will encourage our guests to do so as well.

And don’t forget to sign up for our email list here.